Okavango

Living in a Zoo -- as the Exhibit

“Don’t worry. Those fuel gauges haven’t worked for years. They read empty even when they’re full,” the pilot said as we taxied toward the runway at the Maun Airport. He tapped each gauge with his finger as if to assure us, “See, they really are broken.”

We had just parked our rental car in Maun, Botswana, after driving for two days from Windhoek, Namibia. We were now headed on a one-hour 3-passenger plane flight to a remote island somewhere in the middle of the Okavango Delta. My son, Mike, was in the co-pilot’s seat (staring at the fuel gauge!), my wife and I were in the second pair of seats. And in the back, in seats fashioned extemporaneously from the baggage on board were two employees of the camp where we were now headed.

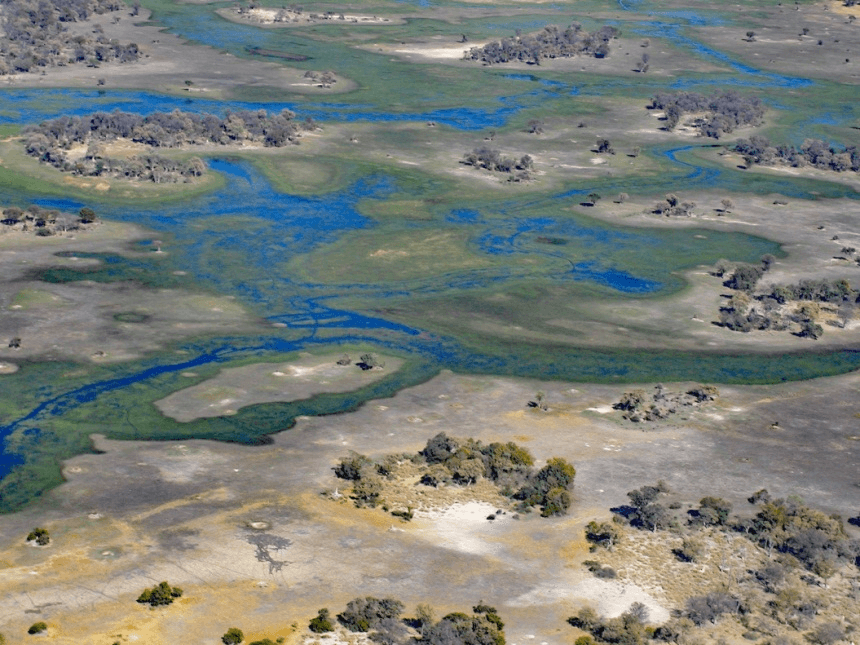

The trip over the delta was spectacular. We could see huge herds of wildebeests running across the dry patches of land, into the ever-present capillary-like waters, and then back onto another dry patch. Okavango Delta is the world’s largest inland river delta; during the wet season, it is approximately 21,000 square miles (55,000 sq km). Instead of flowing into the ocean, the Okavango River, meanders from Angola, through Namibia, and into a huge inland alluvial fan, where the water sits until it either evaporates or sinks into an underwater crevasse along a fault line. The geo-physical characteristics are such that a large quantity of water remains all year around on the surface. The remoteness of this huge area has enabled many species of animals to thrive in relative isolation from man.

To accommodate tourists, 50 or so camps have been established in the Delta, at a wide variety of prices/night. We stayed at Semetsi Camp, which was priced at around $300 per night per person, at roughly the midpoint of the range. Semetsi consisted of around 15 permanent tents spread out in the forest on an island in the Delta. Ours was perched in a tree.

Mike was in another tent around 25 feet away. The entire camp was surrounded by a tall, electric, barbed wire fence, so that we felt like we were in a zoo, only we were the ones in the cage. The area around the camp was teeming with flora and fauna of all kinds. We were located on a small island called Ntswi, pretty much covered by forest (except of course for the cleared area that served as a runway). The waters all around us were mostly covered by lilies and reeds. Atop every reed was a dragonfly.

Here is what a typical day at Semetsi looked like:

- Wake around 7am to a healthy buffet breakfast served in a common building.

- 8am get picked up by local guides in their mokoros (dugout canoes). Since the rule is no more than two guests per guide, Ginny and I were in one mokoro with our guide named Moite, and Mike was in his own mokoro with his guide named Eric. The guides propelled their mokoros quietly using poles (in a fashion similar to the gondola drivers in Venice). Using this technique, they are capable of approaching large mammals without startling them. In a typical morning, we would spend 4 or 5 hours poling around the marsh.

- In early afternoon, return to camp, eat another hearty meal, and then relax around camp for a few more hours.

- As the sun started to descent, Moite and Eric would return and take us on another (usually 2-3 hours) trip in the mokoros. This would enable us to view the sunset in the middle of nowhere, and return safely to camp in complete darkness.

- Next would be dinner served in the open air, usually cooked over an open fire.

- A few more hours listening to the many night sounds of the jungle while sipping on cocktails or drinking beer, and then a good night sleep. Each tent had two beds and a pot (for night time bathroom needs). Each group of 3-4 tents also had a communal bathroom with showers, toilets, sink, etc., all with no roof. The host told us that we could walk out of our tents to the bath-“house” if we wanted to, but did not recommend it; he preferred to allow the animals of the night roam freely around camp.

All the guides at Semetsi Camp (and I suspect at the other Okavango Delta camps as well) are locals who grew up and still live in small villages within the Delta. They have spent their entire lives living with the animals of the land. One of the things we loved about them was that they carried no weapons; we had recently had an opportunity to spend a few weeks on safari in South Africa, and there all the rangers carried rifles to protect the tourists from the animals. In contrast, these guides knew the animals; they knew their behaviors, and they knew how close we could get to each species without provoking an attack. Once we understood this, all three of us felt far safer with these guides than the ones in South Africa.

On our first excursion in the mokoros, the two guides started clicking and whistling to communicate something to each other without disturbing the local fauna. They had both heard a bird chirp a quarter-mile or so away, a bird they knew lived only on the back of a hippopotamus. By following the sound, they would find the hippo. I was doubtful. Having been raised in New York City, I just could not fathom that a human could develop such astute hearing skills and be able to determine the exact location of a large mammal by such means. After 30 minutes of poling, we started to hear belches and snorts of our quarry. And then, as we turned a corner in the meandering waters, there it was. It was a huge female with two offspring. We sat there quietly taking photos for a half-hour or so. I asked Moite if we could get a bit closer (to get a better photo) and he respectfully (and smartly!) declined.

In the middle of our first night at Semetsi, we were awoken by the sound of trees crashing all around us. A local herd of elephants had broken down the barrier fence to taste the trees within the compound . . . trees that had not been eaten by elephants in quite a while. As they crashed and stomped around us, I put on my glasses and peered out our tent door toward Mike’s tent. I saw nothing! I quietly but anxiously reported to my wife that Mike’s tent had disappeared. We assumed the worst, that an elephant had destroyed his tent. Now, we both stared out the tent door trying to figure out why we saw nothing in the direction of where Mike’s tent had been. After a few minutes, we heard more crashing and Mike’s tent suddenly reappeared. Apparently, a large bull elephant had been standing between our tents; we had been staring at the side of an elephant when we thought we were seeing “nothing.” It brought forth memories of the old joke about five people each touching an elephant, and each declaring a different characteristic based on the part of the elephant being touched.

During the following day’s mokoro trip, our guide smelled fresh kill. We docked on an island and we followed him as he tracked the smell. After hiking around 45 minutes or so, we saw a female lion walking away stealthily with some hapless quarry’s leg hanging from her mouth. We continued to walk in the direction from whence the lion had emerged. Soon, Moite asked us all to duck down behind a small hillock and we carefully peered over the top. There was the fresh kill, about 200 feet from our position. A few lions were sitting around eating their selected anatomical parts. There were also a dozen or so black-backed jackals hanging around. Whenever they thought it might be safe, the jackals would run up to the kill, grab something fast, and then dart away with their trophy, hoping that the lions didn’t notice, or at least didn’t care enough to attack them. On occasion, a jackal would run toward the kill, and then run away without even a morsel of food, perhaps spooked by the lions, or perhaps self-spooked by their own dangerous act. As we peered over our hillock, one of the jackals came running right toward us after an aborted attempt to get a bite. Our guide sensed us all tensing up, so he signaled to us to stay still and be quiet. We did. The jackal ran to the top of the hillock, looked us right in the eyes from his position around 15 feet from us, and darted away. I was sure glad that the guide knew the jackal would not attack a human in such a situation.

The next afternoon, Moite asked if we would like to see his village. We answered enthusiastically in the affirmative. After around 30 minutes of poling, we arrived. We spent an hour walking around the village meeting his friends and neighbors. The children were very frightened by our presence. Although all three of us love children and usually have no difficulty relating to them (I even got down on the ground to be with them at “their level”), half the children hid behind their parents or burst into tears whenever we looked at them. We asked the adults about this odd behavior. It seems that the parents tell their little ones that white people are scary (perhaps evil?), and that we might steal them away from their parents. Mystery solved. But we found this situation a bit disconcerting. As we strolled around the village, we met one whittler who carved elephants out of local wood (Mike bought one and still has it displayed in his Colorado home) as well as a blind man playing a homemade percussion instrument consisting of a few pieces of wood and five metal spokes that he could twang. The instrument was for sale. I don’t recall why I declined to buy it, but now in retrospect I wish I had.

Our days at Semetsi passed quickly. Living with the zebras, giraffes, lions, jackals, elephants, and baboons became almost commonplace. The herbivores seemed to hardly notice our presence. Those on top of the food chain rarely took notice of us; fortunately they were not so hungry.

Semetsi shares Ntswi Island with another tent resort called Gunn’s Camp. We’ve been told that the two are owned by the same company and that Gunn’s is the more upscale of the two. To learn more about Okavango Delta lodges, visit www.okavangodelta.com/accommodation.

© Alan M. Davis

If you enjoyed this story, consider buying my book,

Unusual Africa: Traveling on the Edge. It contains this and twelve other stories of our adventures in Africa.

Contact Him

To contact him at Offtoa:

email: adavis(at)offtoa.com

phone: 719-232-1938 (cell), 719-425-8858 (office)

To contact him for other reasons:

email: aldavis171(at)gmail.com

phone: 719-232-1938 (cell)